Copywriting gems from a hundred-year-old Sears catalog

Sears, Roebuck & Company, which filed for bankruptcy last year, started its life as a mail-order firm in 1892, the Amazon of its time.

The early success of the company is often attributed to its co-founder’s copywriting skills. Richard Warren Sears was a railroad station agent in Minnesota when in 1886 his station received an unsolicited shipment of gold watches for a local jeweler, who refused it. Sears saw an opportunity and agreed with the wholesaler to sell them himself, in six months making a profit larger than his railroad salary. He then founded the company to sell watches and jewelry via advertisements in publications and by mailing flyers, and later started a catalog, for which Sears wrote every line of copy. He retired in 1908, but the tradition of good copywriting continued, helping the company become the largest retailer in the world.

“Don’t be afraid you will make a mistake in making out the order,” stated the ordering instructions from the 1912 catalog, “We receive hundreds of orders every day from young and old, who never before sent away orders for goods. We are accustomed to handling all kinds of orders.”

“Write us in your own way, in any language. We have translators who read all languages. Don’t worry if you think your writing is poor. We will be able to read it and your goods will be promptly sent.”

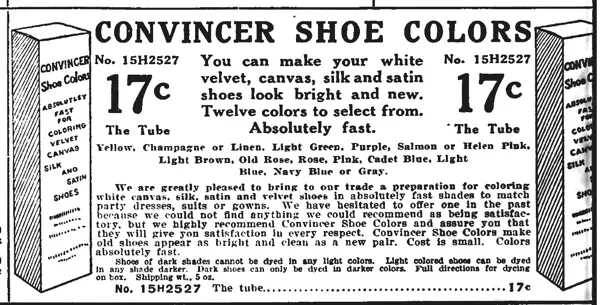

The catalog had more than one thousand two hundred pages filled with pictures, descriptions, and prices for various goods. Each item had a unique sales copy: some short and simple, some elaborate, persuading the customer to order it.

Sears Roebuck’s message was that their prices were low compared to competitors (“the real value of this book is plainly shown in every price quotation”) and the quality was good. Nothing groundbreaking, anyone could claim the same. What’s interesting is how their copywriting and the arrangement of items reinforced these points.

The catalog begins with the cheapest two-cent goods (about fifty cents today), then continues with four-cent items, six-cent, eight, and twelve.

“How Much Money Can You Save on These Items? Your attention is directed to this and the following nine pages where we show several hundred everyday useful household articles, and especially do we ask you to carefully compare the prices at which we offer these goods as against the prices the same goods sell for in stores generally. This quickly gives you an idea of the money saving possibilities shown on every page in this entire catalog.”

The instructions on top ask to order at least twelve items from those pages “to make it a profitable shipment”.

These first pages with lowest prices are important for establishing the low-cost part of the message. The copy for items establishes the quality part. A 2-cent steel can opener is not just a cheap can opener. It’s “a good one”.

A nine-cup deep muffin pan is “made of heavy weight tin” (contrasting with low-quality pans that are made of lightweight tin).

A kitchen knife has “well-finished cocobolo handle” (low-quality knifes have handles made of rough soft wood).

A coffee canister is “double seamed and nicely decorated” (low-quality canisters are single seamed and omit decorations).

Shears feature a “patent adjuster” (not some generic adjuster).

Almost every item has a feature that highlights its quality. When an item has no such feature, reader’s attention is drawn to the fact that it is of better quality or usually sells for more.

A hollow handle tool set is “the best ever offered at anywhere near this price”.

A 12-cent steel spider skillet “usually sells for 25 cents”.

An 8-cent pipe is “20-cent value”.

The catalog continues with hundreds of sections: clothing, toys, jewelry, musical instruments, farm equipment, lumber, firearms, bicycles and even automobiles (they also sold kit houses via a separate catalog!) The index of categories alone occupied sixteen pages set in a tiny font.

To convince customers that they should order from Sears Roebuck, the company positioned itself as a trustworthy intermediary between buyers and manufacturers. They have selected only the best goods to sell:

“We have carefully examined all makes of mattress pads and have no hesitancy in recommending this line as embodying all the desirable features in mattress pads.”

“The most practical and the handiest shaving mirror we have ever seen.”

They import from the best places:

“We import these clippers from Solingen, Germany, the greatest cutlery center in the world, where the finest cutlery is made.”

They make custom orders with manufacturers:

“This Japanese Silk is a pure all silk quality. It is dyed to our order and we know that it will wear to your satisfaction.” (These weren’t empty words, by the way, they even sold automobiles from 1908 until 1912, custom-produced by Lincoln Motor Car Works to Sears Roebuck order.)

They recommend products:

“All silk Messalines are always stylish and popular. This is an exceptionally good grade, soft and pliable and has a very high finish. It will wear very well and make splendid waists, dresses, or may be used for millinery or trimming purposes. We can recommend nothing better in a medium priced messaline.”

They don’t offer products until they find the ones they like:

“We are greatly pleased to bring to our trade a preparation for coloring white canvas, silk, satin and velvet shoes in absolutely fast shades to match party dresses, suits or gowns. We have hesitated to offer one in the past because we could not find anything we could recommend as being satisfactory, but we highly recommend Convincer Shoe Colors and assure you that they will give you satisfaction in every respect. Convincer Shoe Colors make old shoes appear as bright and clean as a new pair. Cost is small. Colors absolutely fast.”

They sell exclusive items:

“The only 4½-ounce silverode case manufactured in the World. We have them. You cannot buy them elsewhere.”

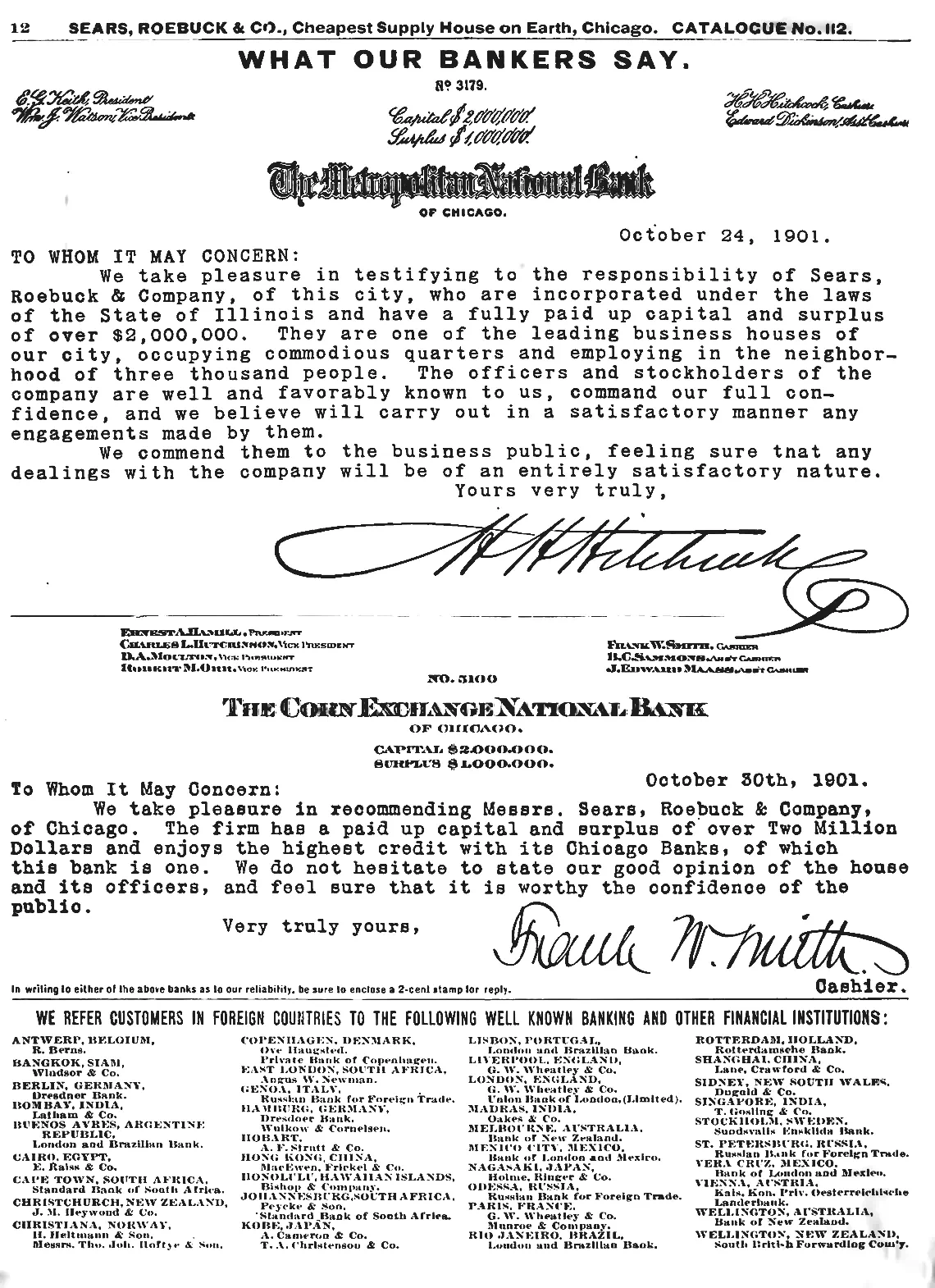

These were some of examples of a carefully crafted copy, but it goes beyond product descriptions. In earlier catalogs, to establish the fact that the company is reputable, Sears Roebuck even included references from their bankers.

Sears Roebuck was not the first or the only mail-order company, but it was the most successful. Their catalogs were everywhere. (Yes, everywhere: when in the 1930s the company started printing catalogs on glossy paper, they received a lot of complaints because it was harder to use as a toilet paper.)

The general catalog business was closed in 1993, with the company focusing on retail stores, the first of which opened in 1925. Sears filed for bankruptcy in 2018 and is soon to be restructured or liquidated. The legacy they left — the amazing catalogs — will survive for us to learn from (some early catalogs are available on the Internet Archive).